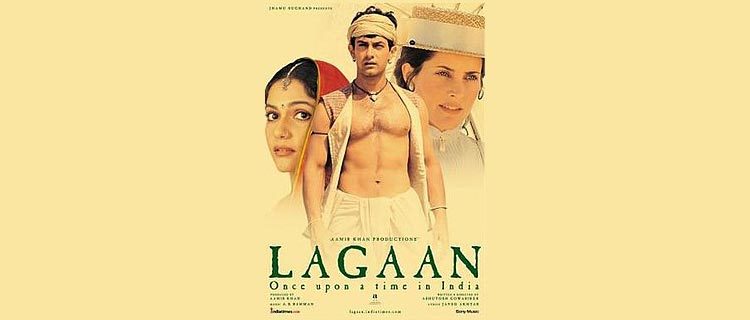

In the 2001 epic film Lagaan, villagers from a small Indian community pull together to inflict a symbolic defeat on the cruel and greedy British Raj. Today taxation and cricket are still alive and well in both countries, and to a lesser extent so is trade. In 2019, Britain and India should not only continue with their trading links but build on them. Citizens and small / medium sized businesses from both countries could develop new trading networks that outpace large corporations and governments. They should do this not just to enrich modern-day merchants, but also for civic benefit as well.

Whatever your views on the Raj era (when trade was the overriding reason for the British presence in India), the extent of direct political control from London was a veneer that lasted for a relatively short period – from the mid-1800s to 1947. But many Indians have good reason to resent this imperial period (and a significant number of Britons also hold negative views). By one important measure – Gross Domestic Product – the Indian economy grew by just 19% in that time, compared to 134% in Britain.

Today however, both countries could benefit substantially by moving on from a Raj focus and grasping future potential opportunities. From Bengaluru, Subhasish Ghosh’s view is “it is high time we stopped blaming the Britishers for everything. We are still building statues and wanting our Kohinoor back. Move on!” Vivek Bhatt goes further – “please learn from the past and carry the learnings to build a progressive future.”

British-Indian bilateral trade remains significant – as recently as 2015 it was valued at £16.33bn, with over 800 Indian companies operating in Britain. But the future should be so much more, with civic as well as trade benefits flowing to both populations. Both countries should capitalise (literally) on opportunities presented by youthful multiple cultures inside their respective borders, and distribute the dividends of opening up trade to all citizens. Britain has a sizeable population of people with Indian heritage (1.45 million according to ABPL), while India herself welcomes as many as 800,000 British visitors every year (with over 30,000 Britons living in India). This is a ready-made civic network that should be developed much further.

Instead of the Raj, British and Indian citizens could see a new relationship as non-imperial, non-militaristic (except for defensive purposes) and strongly focussed on small / medium sized businesses (SMBs) and civic enrichment from trade.

Instead of wheat, jute, tea and textiles, trade could develop from modern “raw materials” – ideas, knowledge, high standards, software and digital technology. From these, new goods and services could flow across physical and virtual networks, to populations that have a youthful urban focus but also a more prosperous and open rural hinterland. Here’s some examples:

- Apps for citizens – opening up opportunities for sharing a wide range of information, mobile analysis and improved e-commerce. Both countries already use apps a lot (Indian smartphone users for example have an average of 51 apps installed on their devices, regularly using 24 of them). Both can boast highly skilled app development and maintenance organisations (like Questionbang, Quy Technology and Waracle). But for key official information, Indian citizens are better served than their British counterparts (Umang– a single app for citizens to access pan-government services – has been well received. Rachit Tyagi comments “another example which demonstrates that our government is listening to the public and making attempts to solve some actual grass root level problems”). Indian developers who’ve created and maintained government apps could be well placed to export their expertise to Britain, where the HMRC tax app remains an isolated example, and others aimed at improving child literacy and getting EU citizens to apply for settled status have yet to be rolled out.

- Frugally-engineered medical services – or coming up with smart, cheap solutions for citizens’ healthcare problems. British innovations are often expensive, whereas Indian healthcare professionals have been described by Navi Radjou as “masters of the art of doing more with less” – finding technology that just works, and not getting distracted by hype that delivers little.

One British doctor, Alex Yeates, came across an example in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in Hyderabad. There, staff use technologies such as remote camera monitoring of ICU equipment, coupled with the WhatsApp messaging service (free, with end-to-end encryption), to share patient notes and scans. Highly trained ICU nurses and clinicians manage and monitor multiple wards in remote locations, delivering critical care to patients who previously had little access to it. Indian organisations should continue looking to expand their medical service offerings to Britain – potentially by further leveraging BAPIO’s (British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin) encouragement for strengthened healthcare infrastructure and greater two-way investment. Better workforce planning and improved infrastructure for elderly citizens’ care would be particular prizes.

- Investment-led skills development – helping citizens get their desired jobs, especially in the age of digital technologies. One commentator, Atul Raja, is concerned India doesn’t have the skilled workforce required to fuel economic growth – and cites reduced government spending on education (down from 4.4% of GDP in 1999 to 3.7% in 2017) as a reason. But does government alone have all the answers? No. In Britain, a mixture of organisations from both industry and education is playing a leading role in re-skilling individuals and communities. Domestic success has led to expansion of support for skills development in India. Following on from Mott Macdonald (educating 100,000 Indian school students every year in energy saving) and Reckitt Benckiser (training investment in India increased by 50% from 2017 to 2020), British SMBs associated with fintech, cyber security and smart cities are now working in India to “unlock its future potential, and deliver high-skilled jobs and economic growth in both countries” (Matt Hancock). Academic institutions have also made investments too – some small (early career scientists from Cambridge University have recently completed a month-long 10,000 mile VIGYANshaala – ‘classroom of science’- tour of India, bringing hands-on science from Cambridge laboratories to 5,000 school children), some larger (the University of London currently has 1,000 students in India studying towards a range of qualifications via three established teaching centres). British organisations should continue contributing to civic benefits in India with further investment-led skills developments.

- High quality human resource (HR) services – helping to develop flexible employment models. British organisations have had notable successes in delivering HR services to benefit domestic employers, employees and wider communities – an OECD survey of 15 countries facing future skills shortages found Britain was second best off (with only 12% of firms with skills shortages). India was second worse off (64%). Successful HR services that could be exported to India include:

- Implementing high quality online job opportunity, skill development programme and recruitment channels

- Standards based in-service and vocational training to upgrade workforce skills

- Career counselling and mentoring services

More challenging would be the opportunity to increase female labour participation (for example by promoting generous maternity leave and other female-friendly workplace policies). To improve the chances of British service providers replicating their home success, India could help herself by removing legal constraints and excessive government labour regulation, including for British providers setting up training institutions. In turn, British organisations would do well to recognise the importance of regional languages and pricing that reflects local purchasing power. With these in mind they could build on the success of EY, Willis Towers Watson, TMF Group and others by providing HR services to India that are high quality, and benefit many.

These examples of potential new trade would disproportionately help young people. That’s both welcome and unsurprising. In India, half the population of 1.3 billion is below the age of 25. In Britain, young workers face a prospect of funding the care and pensions of an ageing population: the number of people of pension age is set to increase by 33% by mid-2039, with the number of working age people only rising by 11%.

Citizens are often in front of large corporations and government when it comes to seeing opportunities and moving forward. They can be quick to network, and through SMBs, quick to build trade. It’s to the citizens and SMBs, especially young ones, of both Britain and India that we should look if we want to grow trade successfully and bring benefits to the many. We should be moving on from Lagaan.